Research into the possibly

problematic aspects of gaming is a hot topic. But most studies in this area have

focused on gamers in Europe and North America. So a recent article in

Nature Scientific Reports, featuring

data from over 10,000 African gamers, would seem to be an important landmark

for this field. However, even though I am an outsider to gaming research, it

seems to my inexpert eye that this article may have a few wrinkles that need

ironing out.

Let’s start with the article

reference. It has 16 authors, and the new edition of the APA Publication Manual

says that we now have to list

up to 20 authors’ names in a reference,

so let’s take a deep breath:

Etindele Sosso, F. A., Kuss, D. J.,

Vandelanotte, C., Jasso-Medrano, J. L., Husain, M. E., Curcio, G., Papadopoulos,

D., Aseem, A., Bhati, P., Lopez-Rosales, F., Ramon Becerra, J., D’Aurizio, G., Mansouri,

H., Khoury, T., Campbell, M., & Toth, A. J. (2020). Insomnia,

sleepiness, anxiety and depression among different types of gamers in African

countries.

Nature Scientific Reports,

10, 1937.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58462-0

(The good news is that it is an open

access article, so you can just follow the DOI link and download the PDF file.)

Etindele Sosso et al. (2020)

investigated the association between gaming and the four health outcomes

mentioned in the title. According to the abstract, the results showed that “problematic

and addicted gamers show poorer health outcomes compared with non-problematic

gamers”, which sounds very reasonable to me as an outsider to the field. A

survey that took about 20 minutes to complete was e-mailed to 53,634

participants, with a 23.64% response rate. After eliminating duplicates and

incomplete forms, a total of 10,566 gamers were used in the analyses. The “type

of gamer” of each participant was classified as “non-problematic”, “engaged”,

“problematic”, or “addicted”, depending on their scores on a measure of gaming

addiction, and the relations between this variable, other demographic

information, and four health outcomes were examined.

The 16 authors of the Etindele

Sosso et al. (2020) article report affiliations at 12 different institutions in

8 different countries. According to the “Author contributions” section, the

first three authors “contributed equally to this work” (I presume that this

means that they did the majority of it); 12 others (all except Papadopoulos, it

seems) “contributed to the writing”; the first three authors plus Papadopoulos

“contributed to the analyses”; and five (the first three authors, plus Campbell

and Toth) “write [sic] the final form of the manuscript”. So this is a very

impressive international collaboration, with the majority of the work apparently

being split between Canada, the UK, and Australia, and it ought to represent a

substantial advance in our understanding of how gaming affects mental and

physical health in Africa.

Funding

Given the impressive set of authors

and the large scale of this international project (data collection alone took

19 or 20 months, from November 2015 to June 2017), it is somewhat surprising that

Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) article reports no source of funding. Perhaps

everyone involved contributed their time and other resources for free, but there

is not even a statement that no external funding was involved. (I am quite

surprised that this last element is apparently not mandatory for articles in

the Nature family of journals.) The administrative

arrangements for the study, involving for example contacting the admissions

offices of universities in nine countries and arranging for their e-mail lists

to be made available, with appropriate guarantees that each university’s and

country’s standards of research ethics would be respected, must have been

considerable. The participants completed an online questionnaire, which might

well have involved some monetary cost, whether directly paid to a survey

hosting company or using up some part of a university’s agreed quota with such

a company. Just publishing an Open Access article in Nature Scientific Reports costs, according to the journal’s web

site, $1,870 plus applicable taxes.

Ethical approval

One possible explanation for the absence

of funding information—although this would still constitute rather sloppy

reporting, since as noted in the previous paragraph funding typically doesn’t

just pay for data collection—might be if the data had already been collected as

part of another study. No explicit statement to this effect is made in the Etindele

Sosso et al. (2020) article, but at the start of the Methods section, we find

“This is a secondary analysis of data collected during the project MHPE

approved by the Faculty of Arts and Science of the University of Montreal

(CERAS-2015-16-194-D)”. So I set out to look for any information about the

primary analysis of these data.

I searched online to see if

“project MHPE” might perhaps be a large data collection initiative from the

University of Montreal, but found nothing. However, in the lead author’s

Master’s thesis, submitted in March 2018 (full text PDF file available

here—note

that, apart from the Abstract, the entire document is written in French, but

fortunately I am fluent in that language), we find that “MHPE” stands for

“Mental Health profile [

sic] of

Etindele” (p. 5), and that the research in that thesis was covered by a

certificate from the ethical board of the university that carries exactly the

same reference number. I will therefore tentatively conclude that this is the

“project MHPE” referred to in the Etindele Sosso et al. (2020) article.

However, the Master’s thesis

describes how data were collected from a sample (prospective size,

12,000–13,000; final size 1,344) of members of the University of Montreal

community, collected between November 2015 and December 2016. The two studies—i.e.,

the one reported in the Master’s thesis and the one reported by Etindele et. al

(2020)—each used five measures, of which only two—the Insomnia Severity Index

(ISI) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)—were common to both.

The questionnaires administered to the participants in the Montreal study

included measures of cognitive decline and suicide risk, and it appears from p.

27, line 14 of the Master’s thesis that participants were also interviewed

(although no details are provided of the interview procedure). All in all, the

ethical issues involved in this study would seem to be rather different to

those involved in asking people by e-mail about their gaming habits. Yet it

seems that the ethics board gave its approval, on a single certificate, for the

collection of two sets of data from two distinct groups of people in two very

different studies: (a) a sample of around 12,000 people from the lead author’s

local university community, using repeated questionnaires across a four-month

period as well as interviews; and (b) a sample of 50,000 people spread across

the continent of Africa, using e-mail solicitation and an online questionnaire.

This would seem to be somewhat unusual.

Meanwhile, we are still no nearer

to finding out who funded the collection of data in Africa and the time taken

by the other authors to make their (presumably extensive, in the case of the

second and third authors) personal contributions to the project. On p. 3 of his

Master’s thesis, the author thanks (translation by me) “The Department of

Biological Sciences and the Centre for Research in Neuropsychology and

Cognition of the University of Montreal, which provided logistical and

financial support to the success of this work”, but it is not clear that “this

work” can be extrapolated beyond the collection of data in

Montreal to include the African project. Nor do we have any more idea about why

Etindele Sosso et al. (2020) described their use of the African data as a "secondary analysis", when it seems, as far as I have been able to establish,

that there has been no previously published (primary) analysis of this data set.

Results

Further questions arise when we

look at the principal numerical results

of Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) article. On p. 4, the authors report that “4

multiple linear regression analyses were performed (with normal gaming as

reference category) to compare the odds for having these conditions [i.e.,

insomnia, sleepiness, anxiety, and depression] (which are dependent variables)

for different levels of gaming.” I’m not sure why the authors would perform

linear, as opposed to logistic, regressions to compare the odds of someone in a

given category having a specific condition relative to someone in a reference

category, but that’s by no means the biggest problem here.

Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) Table 3 lists, for each of the four

health outcome variables, the regression coefficients and associated test

statistics for each of the predictors in their study. Before

we come to these numbers for individual variables, however, it is worth looking

at the R-squared numbers for each model, which range from .76 for depression to

.89 for insomnia. Although these are actually labelled as “ΔR2”, I

assume that they represent the total variance explained by the whole model,

rather than a change in R-squared when “type of gamer” is added to the model

that contains only the covariates. (That said, however, the sentence “Gaming

significantly contributed to 86.9% of the variance in insomnia, 82.7% of the

variance in daytime sleepiness and 82.3% of the variance in anxiety [p <

0.001]” in the Abstract does not make anything much clearer.) But whether these

numbers represent the variance explained by the whole model or just by the

“type of gamer” variable, they constitute remarkable results by any standard. I

wonder if anything in the prior sleep literature has ever predicted 89% of the

variance explained by a measure of insomnia, apart perhaps from another measure

of insomnia.

Now let’s look at the details of

Table 3. In principle there are seven variables (“Type of Gamers [sic]” being the main one of interest, plus

the demographic covariates Age, Sex, Education, Income, Marital status, and Employment

status), but because all of these are categorical, each of the levels except

the reference category will have been a separate predictor in the regression,

giving a total of 17 predictors. Thus, across the four models, there are 68

lines in total reporting regression coefficients and other associated statistics.

The labels of the columns seem to be what one would expect from reports of

multiple regression analyses: B (unstandardized regression coefficient), SE

(standard error, presumably of B), β (standardized regression coefficient), t

(the ratio between B and SE), Sig (the p

value associated with t), and the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence

interval (again, presumably of B).

The problem is that none of the actual

numbers in the table seem to obey the relations that one would expect. In fact

I cannot find a way in which any of them make any sense at all. Here are the

problems that I identified:

- When I compute the ratio B/SE, and compare it to column

t (which should give the same ratio), the two don’t even get close to being

equal in any of the 68 lines. Dividing the B/SE ratio by column t gives results

that vary from 0.0218 (Model 2, Age, 30–36) to 44.1269 (Model 1, Type of Gamers,

Engaged), with the closest to 1.0 being 0.7936 (Model 4, Age, 30–36) and 1.3334

(Model 3, Type of Gamers, Engaged).

- Perhaps SE refers to the standard error of the standardized regression coefficient (β),

even though the column SE appears to the left of the column β? Let’s divide β

by SE and see how the t ratio

compares. Here, we get results that vary from 0.0022 (Model 2, Age, 30–36) to

11.7973 (Model 1, Type of Gamers, Engaged). The closest we get to 1.0 is with

values of 0.7474 (Model 3, Marital Status, Engaged) and 1.0604 (Model 3,

Marital Status, Married). So here again, none of the β/SE calculations comes

close to matching column t.

- The p values

do not match the corresponding t

statistics. In most cases this can be seen by simple inspection. For example,

on the first line of Table 3, it should be clear that a t statistic of 9.748 would have a very small p value indeed (in fact, about 1E−22) rather than .523. In many

cases, even the conventional statistical significance status (either side of p = .05) of the t value doesn’t match the p value. To get an idea of this, I made

the simplifying assumption (which is not actually true for the categories “Age:

36–42”, “Education: Doctorate”, and “Marital status: Married”, but individual

inspection of these shows that my assumption doesn’t change much) that all

degrees of freedom were at least 100, so that any t value with a magnitude greater than 1.96 would be statistically

significant at the .05 level. I then looked to see if t and p were the same

side of the significance threshold; they were not in 29 out of 68 cases.

- The regression coefficients are not always contained

within their corresponding confidence intervals. This is the case for 29 out of

68 of the B (unstandardized) values. I don’t think that the confidence

intervals are meant to refer to the standardized coefficients (β), but just for

completeness, 63 out of 68 of these fall outside the reported 95% CI.

- Whether the regression coefficient falls inside the 95%

CI does not correspond with whether the p

value is below .05. For both the

unstandardized coefficients (B) and the standardized coefficients (β)—which,

again, the CI probably doesn’t correspond to, but it’s quick and cheap to look

at the possibility anyway—this test fails in 41 out of 68 cases.

There are some further concerns

with Table 3:

- In the third line (Model 1, “Type of Gamers”,

“Problematic”) the value for β is 1.8. Now it is actually possible to have a

standardized regression coefficient with a magnitude above 1.0, but its

existence usually means that you have big multicollinearity problems, and it’s

typically very hard to interpret such a coefficient. It’s the kind of thing

that at least one of the four authors who reported in the "Author contributions" section of the article that they "contributed to the analyses" would normally be expected to pick up on and discuss, but no such discussion is

to be found.

- From Table 1, we can see that there were zero

participants in the “Age” category 42–48, and zero participants in the

“Education” category “Postdoctorate”. Yet, in Table 3, for all four models,

these categories have non-zero regression coefficients and other statistics. It

is not clear to me how one can obtain a regression coefficient or standard

error from a categorical variable that corresponds to zero cases (and, hence,

when coded has a mean and standard deviation of 0).

- There is a surprisingly high number of repetitions of exactly

the same value, typically to 3 decimal places, within the same variable,

category, and absolute value of the statistic from one model to another. For example, the reported

value in the column t for the variable “Age” and category “24–30” is 29.741 in

both Models 1 and 3. For the variable “Employment status” and category

“Employed”, the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval is the same (2.978)

in all four models. This seems quite unlikely to be the result of chance, given

the relatively large sample sizes that are involved for most of the categories

(cf. Brown & Heathers, 2019), so it is not clear how these duplicates could

have arisen.

Table 3 from Etindele et al. (2020), with duplicated values (considering

the same variable and category across models) highlighted with a different colour for each set of duplicates. Two pairs are included where the

sign changed but the digits remained identical; however, p values that were reported as 0.000 are ignored. To

find a duplicate, first identify a cell that is outlined in a particular

colour, then look up or down the table for one or more other cells with the same

outline colour in the analogous position for one or more other models.

The preprint

It is interesting to compare

Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) article with a preprint entitled “Insomnia and

problematic gaming: A study in 9 low- and middle-income countries” by Faustin

Armel Etindele Sosso and Daria J. Kuss (who also appears to be the second

author of the published article), which is available

here.

That preprint reports a longitudinal study, with data collected at multiple time

points—presumably four, including baseline, although only “after one months,

six months, and 12 months” (p. 8) is mentioned—from a sample of people (initial

size 120,460) from nine African countries. This must therefore be an entirely

different study from the one reported in the published article, which did not

use a longitudinal design and had a prospective sample size of 53,634. Yet, by

an astonishing coincidence, the final sample retained for analysis in the

preprint consisted of 10,566 participants, which is exactly the same as the

published article. The number of men (9,366) and women (1,200) was also

identical in the two samples. However, the mean and standard deviation of their

ages was different (M=22.33 years, SD=2.0 in the preprint; M=24.0, SD=2.3 in

the published article). The number of participants in each of the nine

countries (Table 2 of both the preprint and the published article) is also substantially

different for each country between the two papers, and with two exceptions—the

ISI and the well-known Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)—different

measures of symptoms and gaming were used in each case.

Another remarkable coincidence

between the preprint and Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) published article,

given that we are dealing with two distinct samples, occurs in the

description of the results obtained from the sample of African gamers on the

Insomnia Severity Index. On p. 3 of the published article, in the

paragraph describing the respondents’ scores on the ISI, we find: “The internal

consistency of the ISI was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), and each individual

item showed adequate discriminative capacity (r = 0.65–0.84). The area under the receiver operator characteristic

curve was 0.87 and suggested that a cut-off score of 14 was optimal (82.4%

sensitivity, 82.1% specificity, and 82.2% agreement) for detecting clinical

insomnia”. These two sentences are identical, in every word and number, to the

equivalent sentences on p. 5 of the preprint.

Naturally enough, because the

preprint and Etindele Sosso et al.’s (2020) published article describe entirely

different studies with different designs, and different sample sizes in each

country, there is little in common between the Results sections of the two

papers. The results in the preprint are based on repeated-measures analyses and

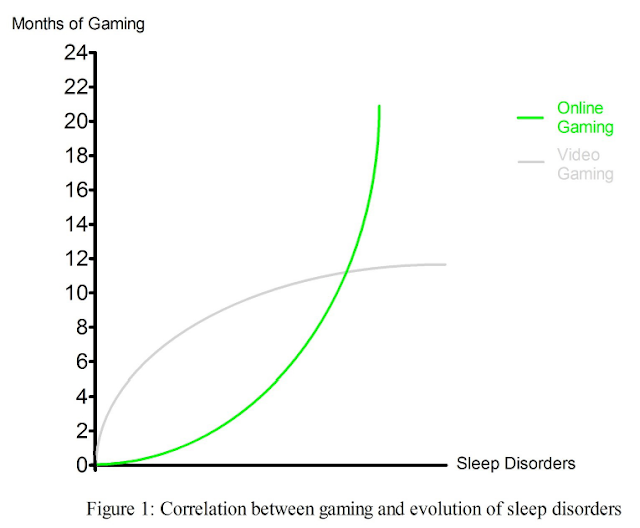

include some interesting full-colour figures (the depiction of correlations in

Figure 1, on p. 10, is particularly visually attractive), whereas the

results of the published article consist mostly of a fairly straightforward

summary, in sentences, of the results from the tables, which describe the

outputs of linear regressions.

Figure 1 from the preprint by

Etindele Sosso and Kuss (2018, p. 10). This appears to use an innovative technique to illustrate the correlation between two variables.

However, approximately 80% of the

sentences in the introduction of the published article, and 50% of the

sentences in the Discussion section, appear (with only a few cosmetic changes)

in the preprint. This is interesting, not only because it would be quite

unusual for a preprint of one study to be repurposed to describe en entirely

different one, but also because it suggests that the addition of 14 authors between the publication of the preprint and the Etindele Sosso et al. (2020) article resulted

in the addition of only about 1,000 words to these two parts of the manuscript.

The Introduction section of the Etindele and Kuss (2018) preprint (left) and the Etindele et al. (2020) published

article (right). Sentences highlighted in yellow are common to both papers.

The Discussion section of the Etindele and Kuss (2018) preprint (left) and the Etindele et al. (2020) article (right). Sentences highlighted in yellow are common to both papers.

Another (apparently unrelated) preprint

contains the same insomnia results

It is also perhaps worth noting that

the summary of the participants’ results on the ISI measure—which, as we saw above,

was identical in every word and number between the preprint and Etindele Sosso

et al. (2020)’s published article—also appears, again identical in every word

and number, on pp. 5–6 of a 2019 preprint by the lead author, entitled

“Insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, anxiety, depression and socioeconomic

status among customer service employees in Canada”, which is available

here [PDF].

This second preprint describes a study of yet another different sample, namely 1,200

Canadian customer service workers. If this is not just another remarkable coincidence,

it would suggest that the author may have discovered some fundamental invariant

property of humans with regard to insomnia. If so, one would hope that both

preprints could be peer reviewed most expeditiously, to bring this important

discovery to the wider attention of the scientific community.

Other reporting issues from the

same laboratory

The lead author of the Etindele

Sosso et al. (2020) article has published even more studies with substantial

numbers of participants. Here are two such articles, which have 41 and 35

citations, respectively, according to Google Scholar:

Etindele Sosso, F. A., & Rauoafi, S. (2016).

Brain disorders: Correlation between cognitive impairment and complex

combination. Mental Health in Family

Medicine, 12, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.25149/1756-8358.1202010

In the 2016 article, 1,344

respondents were assessed for cognitive deficiencies; 71.7% of the participants

were aged 18–24, 76.2% were women, and 62% were undergraduates. (These figures

all match those that were reported in the lead author’s Master’s thesis, so we might

tentatively assume that this study used the same sample.) In the 2017 article,

1,545 respondents were asked about suicidal tendencies, with 78% being aged

18–24, 64.3% women, and 71% undergraduates. Although these are clearly entirely

different samples in every respect, the tables of results of the two studies

are remarkably similar. Every variable label is identical across all three

tables, which might not be problematic in itself if similar predictors were

used for all of the different outcome variables. More concerning, however, is

the fact that of the 120 cells in Tables 1 and 2 that contain statistics (mean/SD

combinations, p values other than

.000, regression coefficients, standard errors, and confidence intervals), 58—that

is, almost half—are identical in every digit. Furthermore, the entirety of Table 3—which shows the

results of the logistic regressions, ostensibly predicting completely different

outcomes in completely different samples—is identical across the two articles

(52 out of 52 numbers). One of the odds ratios in Table 3 has the value 1133096220.169

(again, in both articles). There does not appear to be an obvious explanation

for how this duplication could have arisen as the result of a natural process.

Left: The tables of results from Etindele Sosso and Raouafi

(2016). Right: The tables of results from Etindele Sosso (2017a). Cells highlighted

in yellow are identical (same variable name, identical numbers) in both articles.

The mouse studies

Further evidence that this

laboratory may have, at the very least, a suboptimal approach to quality

control when it comes to the preparation of manuscripts comes from the

following pair of articles, in which the lead author of Etindele Sosso et al.

(2020) reported the results of some psychophysiological experiments conducted on

mice:

Etindele Sosso, F. A., Hito, M. G., & Bern, S. S. (2017). Basic

activity of neurons in the dark during somnolence induced by anesthesia.

Journal of Neurology and Neuroscience,

8(4), 203–207.

https://doi.org/10.21767/2171-6625.1000203

In each of these two articles

(which have 28 and 24 Google Scholar citations, respectively), the neuronal

activity of mice when exposed to visual stimuli under various conditions was

examined. Figure 5 of the first article shows the difference between the firing

rates of the neurons of a sample of an unknown number of mice (which could be as

low as 1; I was unable to determine the sample size with any great level of certainty

by reading the text) in response to visual stimuli that were shown in different

orientations. In contrast, Figure 3 of the second article represents the firing

rates of two different types of brain cell (interneurons and pyramidal cells)

before and after a stimulus was applied. That is, these two figures represent

completely different variables in completely different experimental conditions.

And yet, give or take the use of dots of different shapes and colours, they

appear to be exactly identical. Again, it is not clear how this could have

happened by chance.

Top: Figure 5 from Etindele Sosso (2017b). Bottom: Figure 3

from Etindele Sosso et al. (2017). The dot positions and axis labels appear to

be identical. Thanks are due to Elisabeth Bik for providing a second pair of

eyes.

Conclusion

I find it slightly surprising that

16 authors—all of whom, we must assume because of their formal statements to

this effect in the “Author contributions” section, made substantial

contributions to the Etindele et al. (2020) article in order to comply with the

demanding authorship guidelines of

Nature

Research journals (specified

here)—apparently

failed to notice that this work contained quite so many inconsistencies. It

would also be interesting to know what the reviewers and action editor had to

say about the manuscript prior to its publication. The time between submission

and acceptance was 85 days (including the end of year holiday period), which does not suggest that a particularly extensive revision process took

place. In any case, it seems that some sort of corrective action may be

required for this article, in view of the importance of the subject matter for

public policy.

Supporting files

I have made the following

supporting files available

here:

-

Etindele-et-al-Table3-numbers.xls: An Excel

file containing the numbers from Table 3 of Etindele et al.’s (2020) article,

with some calculations that illustrate the deficiencies in the relations

between the statistics that I mentioned earlier. The basic numbers were

extracted by performing a copy/paste from the article’s PDF file and using text

editor macro commands to clean up the structure.

-

“(Annotated) Etindele Sosso, Raouafi - 2016 - Brain

Disorders - Correlation between Cognitive Impairment and Complex

Combination.pdf” and “(Annotated) Etindele Sosso - 2017 - Neurocognitive

Game between Risk Factors, Sleep and Suicidal Behaviour.pdf”: Annotated

versions of the 2016 and 2017 articles mentioned earlier, with identical

results in the tables highlighted.

-

“(Annotated) Etindele Sosso, Kuss - 2018 (preprint) -

Insomnia and problematic gaming - A study in 9 low- and middle-income

countries.pdf” and “(Annotated) Etindele Sosso et al. - 2020 -

Insomnia, sleepiness, anxiety and depression among different types of gamers in

African countries.pdf” Annotated versions of the 2018 preprint and the

published Etindele et al. (2020) article, with overlapping text highlighted.

-

Etindele-2016-vs-2017.png, Etindele-et-al-Table3-duplicates.png,

Etindele-mouse-neurons.png,

Etindele

Sosso-Kuss-Preprint-Figure1.png, Preprint-article-discussion-side-by-side.png,

Preprint-article-intro-side-by-side.png:

Full-sized versions of the images from this blog post.

Reference

Brown,

N. J. L., & Heathers, J. A. J. (2019). Rounded Input Variables, Exact Test Statistics

(RIVETS): A technique for detecting hand-calculated results in published

research.

PsyArXiv

Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ctu9z

[[ Update 2020-04-21 13:14 UTC: Via Twitter, I have learned that I am not the first person to have publicly questioned the Etindele et al. (2020) article. See Platinum Paragon's blog post from 2020-04-17

here. ]]

[[ Update 2020-04-22 13:43 UTC: Elisabeth Bik has identified two more articles by the same lead author that share an image (same chart, different meaning). See

this Twitter thread. ]]

[[ Update 2020-04-23 22:48 UTC: See my related blog post

here, including discussion of a partial data set that appears to correspond to the Etindele et al. (2020) article. ]]

[[ Update 2020-06-04 11:50 UTC: I blogged about the reaction (or otherwise) of university research integrity departments to my complaint about the authors of the Etindele Sosso et al. article

here. ]]

[[ Update 2020-06-04 11:55 UTC: The Etindele Sosso et al. article has been retracted. The retraction notice can be found

here. ]]