This post is about some issues in the following article, and most notably its dataset:

Mo, C. H., Jachimowicz, J. M., Menges, J. I., & Galinsky, A. D. (2023). The impact of incidental environmental factors on vote choice: Wind speed is related to more prevention‑focused voting. Political Behavior. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09865-y

You can download the article from

here, the Supplementary Information from

here [.docx], and the dataset from

here. Credit is due to the authors for making their data available so that others can check their work.

Introduction

The premise of this article, which was brought to my attention in a direct message by a Twitter user, is that the wind speed observed on the day of an "election" (although in fact, all the cases studied by the authors were referendums) affects the behaviour of voters, but only if the question on the ballot represents a choice between prevention- and promotion-focused options, in the sense of

regulatory focus theory. The authors stated in their abstract that "we find that individuals exposed to higher wind speeds become more prevention-focused and more likely to support prevention-focused electoral options".

This article (specifically the part that focused on the UK's referendum on leaving the European Union ("Brexit") has already been critiqued by Erik Gahner

here.

I should state from the outset that I was skeptical about this article when I read the abstract, and things did not get better when I found a couple of basic factual errors in the descriptions of the Brexit referendum:

- On p. 9 the authors claim that "The referendum for UK to leave the European Union (EU) was advanced by the Conservative Party, one of the three largest parties in the UK", and again, on p. 12, they state "In the case of the Brexit vote, the Conservative Party advanced the campaign for the UK to leave the EU". However, this is completely incorrect. The Conservative Party was split over how to vote, but the majority of its members of parliament, including David Cameron, the party leader and Prime Minister, campaigned for a Remain vote (source).

- At several points, the authors claim that the question posed in the Brexit referendum required a "Yes"/"No" answer. On p. 7 we read "For Brexit, the “No” option advanced by the Stronger In campaign was seen as clearly prevention-oriented ... whereas the “Yes” option put forward by the Vote Leave campaign was viewed as promotion-focused". The reports of result coding on p. 8, and the note to Table 1 on p. 10, repeat this claim. But this is again entirely incorrect. The options given to voters were to "Remain" (in the EU) or "Leave" (the EU). As the authors themselves note, the official campaign against EU membership was named "Vote Leave" (and there was also an unofficial campaign named "Leave.EU"). Indeed, this choice was adopted, rather than "Yes" or "No" responses to the question "Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?", precisely to avoid any perception of "positivity bias" in favour of a "Yes" vote (source). Note also here that, had this change not been made, the pro-EU vote would have been "Yes", and not the (prevention-focused) "No" claimed by the authors. (*)

Nevertheless, the article's claims are substantial, with remarkable implications for politics if they were to be confirmed. So I downloaded the data and code and tried to reproduce the results. Most of the analysis was done in Stata, which I don't have access to, but I saw that there was an R script to generate Figure 2 of the study that analysed the Swiss referendum results, so I ran that.

My reproduction of the original Figure 2 from the article. The regression coefficient for the line in the "Regulatory Focus Difference" condition is B=0.545 (p=0.00006), suggesting that every 1km/h increase in wind speed produces an increase of more than half a percentage point in the vote for the prevention-oriented campaign.

Catastrophic data problems

I had no problem in reproducing Figure 2 from the article. However, when I looked a little closer at the dataset (**) I noticed a big problem in the numbers. Take a look at the "DewPoint" and "Humidity" variables for "Election 50", which corresponds to Referendum 24 (***) in the Supplementary Information, and see if you can spot the problem.

Neither of those variables can possibly be correct for "Election 50" (note that the same issues affect the records for every "State", i.e., Swiss canton):

- DewPoint, which would normally be a Fahrenheit temperature a few degrees below the actual air temperature, contains numbers between 0.401 and 0.626. The air temperature ranges from 45.3 to 66.7 degrees. For the dew point temperatures to be correct would require the relative humidity to be around 10% (calculator), which seems unlikely in Switzerland on a mild day in May. Perhaps these DewPoint values in fact correspond to the relative humidity?

- Humidity (i.e., relative atmospheric humidity), which by definition should be a fraction between 0 and 1, is instead a number in the range from 1008.2 to 1015.7. I am not quite sure what might have caused this. These numbers look like they could represent some measure of atmospheric pressure, but they only correlate at 0.538 with the "Pressure" variable for "Election 50".

To evaluate the impact of these strange numbers on the authors' model, I modified their R script, Swiss_Analysis.R, to remove the records for "Election 50" and obtained this result from the remaining 23 referendums:

Figure 2 with "Election 50" (aka Referendum 24) removed from the model.

The angle of the regression line on the right is considerably less jaunty in this version of Figure 2. The coefficient has gone from B=0.545 (SE=0.120, p=0.000006) to B=0.266 (SE=0.114, p=0.02), simply by removing the damaged data that were apparently causing havoc with the model.

How robust is the model now?

A p value of 0.02 does not seem like an especially strong result. To test this, after removing the damaged data for "Election 50", I iterated over the dataset removing a further different single "Election" each time. In seven cases (removing "Election" 33, 36, 39, 40, 42, 46, or 47) the coefficient for the interaction in the resulting model had a p value above the conventional significance level of 0.05. In the most extreme case, removing "Election 40" (i.e., Referendum 14, "Mindestumwandlungsgesetz") caused the coefficient for the interaction to drop to 0.153 (SE=0.215, p=0.478), as shown in the next figure. It seems to me that if the statistical significance of an effect disappears with the omission of just one of the 23 (****) valid data points in 30% of the possible cases, this could indicate a lack of robustness in the effect.

Figure 2 with "Election 50" (aka Referendum 24) and "Election 40" (aka Referendum 14) removed from the model.

Other issues

Temperature precision

The ambient temperatures on the days of the referendums (variable "Temp") are reported with eight decimal places. It is not clear where this (apparently spurious) precision could have come from. Judging from their range the temperatures would appear to be in degrees Fahrenheit, whereas one would expect the original Swiss meteorological data to be expressed in degrees Celsius. However, the conversion between the two scales is simple (F = C * 1.8 + 32) and cannot introduce more than one extra decimal place. The authors state that "Weather data were collected from www.forecast.io/raw/", but unfortunately that link redirects to a

page that suggests that this source is no longer available.

Cloud cover

The "CloudCover" variable takes only eight distinct values across the entire dataset, namely 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 24, 34, and 38. It is not clear what these values represent, but it seems unlikely that they (all) correspond to a percentage or fraction of the sky covered by clouds. Yet, this variable is included in the regression models as a linear predictor. If the values represent some kind of ordinal or even nominal coding scheme, rather than being a parameter of some meteorological process, then including this variable could have arbitrary consequences for the regression (after all, 24, 34, and 38 might equally well have been coded ordinally as 9, 10, and 11, or perhaps nominally as -99, -45, and 756). If the intention is for these numbers to represent obscured eighths of the sky ("

oktas"), then there is clearly a problem with the values above 8, which constitute 218 of the 624 records in the dataset (34.9%).

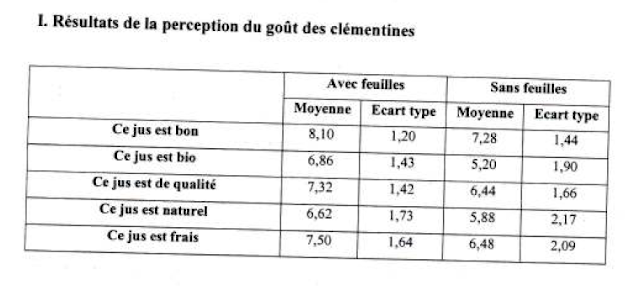

Income

It would also be interesting to know the source of the "Income" data for each Swiss canton, and what this variable represents (e.g., median salary, household income, gross regional product, etc). After extracting the income data and canton numbers, and converting the latter into names, I consulted several Swiss or Swiss-based colleagues, who expressed skepticism that the cantons of Schwyz, Glarus, and Jura would have the #1, #3, and #4 incomes by any measure. I am slightly concerned that there may have been an issue with the sorting of the cantons when the Income variable was populated. The Supplementary Information says "Voting and socioeconomic information was obtained from the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics (Bundesamt für Statistik 2015)", and that reference points to a web page entitled “Detaillierte Ergebnisse Der Eidgenössischen Volksabstimmungen” with URL http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/17/03/blank/data/01.html, but that link is dead (and in any case, the title means "Detailed results of Federal referendums"; such a page would generally not be expected to contain socioeconomic data).

Swiss cantons (using the "constitution order" mapping from numbers to names) and their associated "Income", presumably an annual figure in Swiss francs. Columns "Income(Mo)" and the corresponding rank order "IncRank" are from Mo et al.'s dataset; "Statista" and "StatRank" are from statista.com.

I obtained some fairly recent Swiss canton-level household income data from

here and compared it with the data from the article. The results are shown in the figure above. The Pearson correlation between the two sets of numbers was 0.311, with the rank-order correlation being 0.093. I think something may have gone quite badly wrong here.

Turnout

The value of the "Turnout" variable is the same for all cantons. This suggests that the authors may have used some national measure of turnout here. I am not sure how much value such a variable can add. The authors note (footnote 12, p. 17) that "We found that, except for one instance, no other weather indicator was correlated with the number of prevention-focused votes without simultaneously also affecting turnout rates. Temperature was an exception, as increased temperature was weakly correlated with a decrease in prevention-focused vote and not correlated with turnout". It is not clear to me what the meaning would be of calculating a correlation between canton-level temperature and national-level turnout.

Voting results do not always sum to 1

Another minor point about whatever cleaning has been performed on the dataset is that in 68 out of 624 cases (10.9%), the sum of "VotingResult1" and "VotingResult2" — representing the "Yes" and "No" votes — is 1.01 and not 1.00. Perhaps this is the result of the second number being generated by the first being subtracted from 1.00 when the first number was expressed as a percentage with one decimal place, with both numbers subsequently being rounded and something ambiguous happening with the last digit 5. In any case, it would seem important for these two numbers to sum to 1.00. This might not make an enormous amount of difference to the results, but it does suggest that the preparation of the data file may not have been done with excessive care.

Mean-centred variables

Two of the control variables, "Pressure" and "CloudCover", appear in the dataset in two versions, raw and mean-centred. There doesn't seem to be any reason to mean-centre these variables, but it is something that is commonly done when calculating interaction terms. I wonder whether at some point in the analyses the authors tested atmospheric pressure and cloud cover, rather than wind speed, as possible drivers of an effect on voting. Certainly there seems to be quite a lot of scope for the authors to have wandered around

Andrew Gelman's "Garden of forking paths" in these analyses, which do not appear to have been pre-registered.

Finally, a huge (to me, anyway) limitation of this study is that there is no measure of, or attempt to weight the results by, the population of the cantons. The most populous Swiss canton (Zürich) has a population about 90 times that of the least populous (Appenzell Innerrhoden), yet the cantons all have equal weight in the models. The authors barely mention this as a limitation; they only mention the word "population" once, in the context of determining the average wind speed in Study 1. Of course, the

ecological fallacy [.pdf] is always lurking whenever authors try to draw conclusions about the behaviour of individuals, whether or not the population density is taken into account, although this did not stop the authors from claiming in their abstract that "we find that

individuals [emphasis added] exposed to higher wind speeds become more prevention-focused and more likely to support prevention-focused electoral options", or (on p. 4) stating that "We ... tested whether higher wind speed increased

individual’s [punctuation

sic; emphasis added] prevention focus".

Conclusion

I wrote this post principally to draw attention to the obviously damaging errors in the records for "Election 50" in the Swiss data file. I have also written to the authors to report those issues, because these are clearly in need of urgent correction. Until that has happened, and perhaps until someone else (with access to Stata) has conducted a re-analysis of the results for both the "Swiss" and "Brexit/Scotland" studies, I think that caution should be exercised before citing this paper. The other issues that I have raised in this post are, of course, open to critique regarding their importance or relevance. For the avoidance of doubt, given the nature of some of the other posts that I have made on this blog, I am not suggesting that anything untoward has taken place here, other than perhaps a degree of carelessness.

Supporting files

I have made my modified version of Mo et al.'s code to reproduce Figure 2 available

here, in the file "(Nick) Swiss_Analysis.R". If you decide to run it, I encourage you to use the authors' original data file ("Swiss.dta") from the ZIP file that can be downloaded from the link at the top of this post. However, as a convenience, I have made a copy of this file available along with my code. In the same place you will also find a small Excel table ("Cantons.xls") containing data for my analysis of the canton-level income question.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jean-Claude Fox for doing some further digging on the Swiss income numbers after this post was first published.

Footnotes

(*) Interestingly, the title of Table 1 and, even more explicitly, the footnote on p. 10 ("Remain" with an uppercase initial letter) suggest that the authors may have been aware that the actual voting choices were "Remain" and "Leave". Perhaps these were simplified to "No" and "Yes", respectively, for consistency with the reports of the Scottish independence referendum; but if so, this should have been reported.

(**) I exported the dataset from Stata's .dta format to .csv format using rio::convert(). I also confirmed that the errors that I report in this post were present in the Stata file by inspecting the data structure after the Stata file had been read in to R.

(***) The authors coded the Swiss referendums, which are listed with numbers 1–24 in the Supplementary Information, as 27–50, by adding 26. They also coded the 26 cantons of Switzerland as 51–76, apparently by adding 50 to the constitutional order number (1 = Zürich, 26 = Jura; see

here), perhaps to ensure that no small integer that might creep into the data would be seen as either a valid referendum or canton (a good practice in general). I was able to check that the numerical order of the "State" variable is indeed the same as the constitutional order by examining the provided latitude and longitude for each canton on Google Maps (e.g., "State" 67, corresponding to the canton of St Gallen with constitutional order 17, has reported coordinates of 47.424482, 9.376717, which are in the centre of the town of St Gallen).

(****) I am not sure whether a single referendum in 26 cantons represents 1 or 26 data points. The results from one canton to the next are clearly not independent. I suppose I could have written "4.3% of the data" here.